Normally, Miss Abigail would not be out, still suffering, as she was, from a long bout of the funk. But today, since she had run out of provisions, she had no choice but to walk to Main Street. Having encountered no troubles while making her purchases, Miss Abigail felt unusually buoyant, so decided to window shop.

She found that she could not resist the lonely little cat with the crooked tail in the thrift shop window.

There was something so familiar in the cat’s bewildered look, that Miss Abigail felt like she had known the cat all her life. The cat felt vaguely the same way about Miss Abigail. Within a block of leaving the thrift shop, Miss Abigail named the cat Sheila and by the time they reached Miss Abigail’s house, Sheila was happy with that.

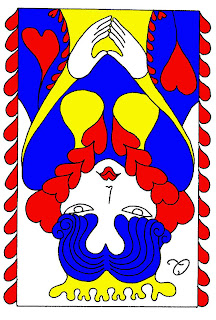

Miss Abigail gave Sheila the place of honor in the curio cabinet.

Suddenly, Miss Abigail felt a stirring inside which she hadn’t felt for so long, she had trouble diagnosing it. But Miss Abigail, being of rare insight, only had to reflect for several long moments to realize that the stirring was the desire to entertain guests. It came as quite a shock to her since she hadn’t had guests for many months. But Miss Abigail was never one to ignore an instinct. She telephoned her friends, plucked rhubarb from her neglected garden for the making of her great grandmother’s rhubarb raisin pie, and set the table with tea cups, saucers, spoons, cream and sugar.

As the guests arrived each was sure to fawn over how well Miss Abigail looked. They had long suspected that their friend was suffering from the funk and wanted to encourage her social behavior. Miss Abigail took the compliments in the most poised way she knew while subtly attempting to draw her friends’ attentions to the curio cabinet. But seeing that all her eye rolling and throat clearing and head tipping was only inspiring looks of queer curiosity in her friends’ faces, Miss Abigail had to resort to more direct methods.

“Have you seen my new cat?” she asked.

Her friends, imagining a warm-blooded creature, capable of leaping, purring, and meowing, were overcome with enthusiasm, thinking that the presence of another living being in the house would be the perfect therapy for Miss Abigail. So when Miss Abigail practically floated to the curio cabinet, and they saw that the object of her statement was nothing but a little bewildered looking stuffed cat with a crooked tail, they were stunned. But the friends, all acutely aware of the fragility of the situation, fawned over the little cat anyway, which made Miss Abigail beam.

Though Sheila was not accustomed to such attentions, Miss Abigail thought she handled her new fame with aplomb. “I think,” Miss Abigail said that night after all her friends had departed, “that Mr. Elliot would appreciate your company.” Mr. Elliot was owner of the town’s bookshop, a benevolant gentleman who, in the months before she fell to the funk, always greeted Miss Abigail at the bookshop door, the corner of his mouth twitching as he offered a gentle collection of poems that he was sure would not damage Miss Abigail’s sensitive constitution.

These books of poems Miss Abigail found lacking in a vital zest, yet she had always been so charmed by his earnest gifts and his nervous ticks that it had not been an unpleasant chore to bake oatmeal raisin cookies and deliver them once a week, on Tuesday mornings, when she knew the bookshop would most likely be devoid of customers. And now that Sheila had helped to lift the gloomy cloud so characteristic of the funk, Miss Abigail could see, by inspecting the calendar hung on the wall, that the following day was indeed a Tuesday. Miss Abigail got right to work, mixing the batter for the cookies.

After they had completely cooled, she carefully wrapped each cookie in wax paper and packed them into a sturdy shirt box, all the while humming Blue Moon since she knew that Sheila would appreciate its rapt sentimentality.